Introduction

Undergraduate course design often seems to go more or less like:

- Select a textbook.

- Before the first lecture, digest the first couple chapters into some lecture notes.

- Present the lecture notes over a week of lectures.

- Assign homework exercises from that portion of the text that was covered that week.

And repeat 2-4 until the end of the allotted time for the course, with some midterms sprinkled in the middle and a final at the end. On its surface, not totally unreasonable; a logically written textbook can scaffold a semester of conversation pretty easily. But:

- Are you sure that textbook & lecture series started in the right place for your learners? Faculty (should) know better than to trust a course's prerequisites to reflect their learners' knowledge - and a workshop instructor has an even foggier picture of where students are coming from.

- Did the homework help deepen students' understanding - or just cement skills by rote?

- How well can you predict what students will know by the end of the course? If the students can't follow the text at the premeditated speed and the instructor's only options are to slow down or abandon her students, learning goals may never be reached.

- What mechanisms exist to give students additional pathways to understanding, beyond what's presented in the book?

These situations and pitfalls are common products of this 'march-through' approach to lesson design. We would like our instruction to be better targeted, more constructive, more reliable and more adaptable - but how?

A couple of tools will let us reach for our ambition. In this unit, we'll learn about reverse instructional design, which will help with targeting and reliability, and about summative vs. formative assessment, which will help our lessons be more constructive and adaptable.

Reverse Instructional Design

Two of the characteristics we want for our lessons are better reliability and better targeting, compared to what we get by stepping linearly through a fixed text from a starting point that may not fit our learners, through content that may be tangential to our key goals, and towards a conclusion at an often arbitrary point in the curriculum imposed by running out of time. If we take reliable learning outcomes as our starting point, a simple line of logic assembles itself.

In order to even attempt to assert that our teaching has a reliable outcome, we must first decide what skill, knowledge or understanding we want our students to acquire, and we must create some way of assessing the students in order to demonstrate that they did indeed assimilate that lesson. At which point we've set up a measurable task for our students and can ask the question, 'what will a student have to master from our lessons before being able to succeed at this task?' - and we can keep asking that question of all the dependencies we identify in this manner, until we arrive at a set of skills & knowledge we believe we can safely assume our students come to us with a priori.

Play that chain backwards in class, and you've got a lesson plan that starts with assumptions about your learners at the per-skill (rather than per-textbook chapter) level, thus being well targeted to your students, and steps efficiently through concepts towards the ultimate learning goal, thus being as reliable as possible. This process is in essence Reverse Instructional Design, and it represents an alternative in lesson design to proceeding linearly between fixed points in a text.

Procedure & Example

A typical implementation of reverse instructional design may go something like this:

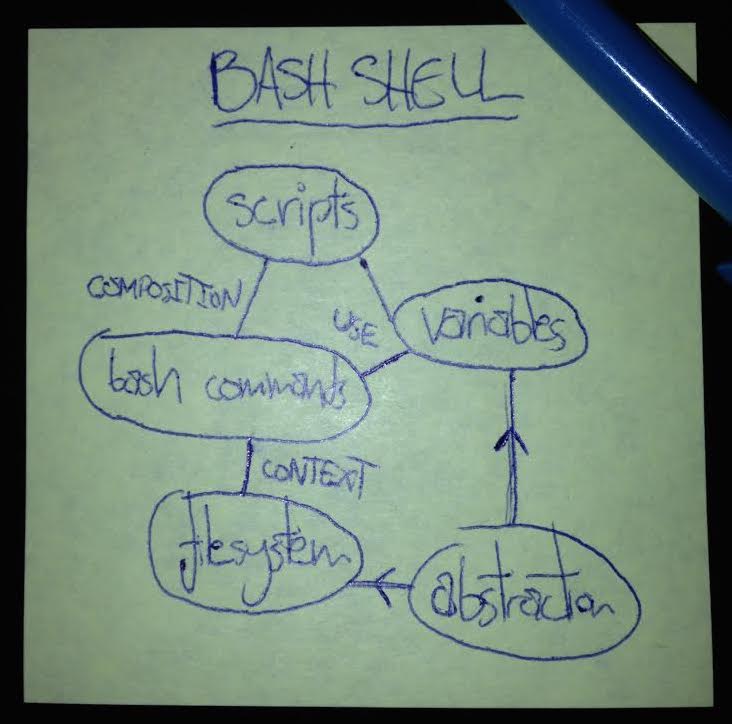

Sketch a Concept Map. As discussed in previous lessons, concept maps are always helpful for laying out a large topic so that connections can be tracked and scope can be controlled. Here's my quickie concept map surrounding some ideas in the bash shell:

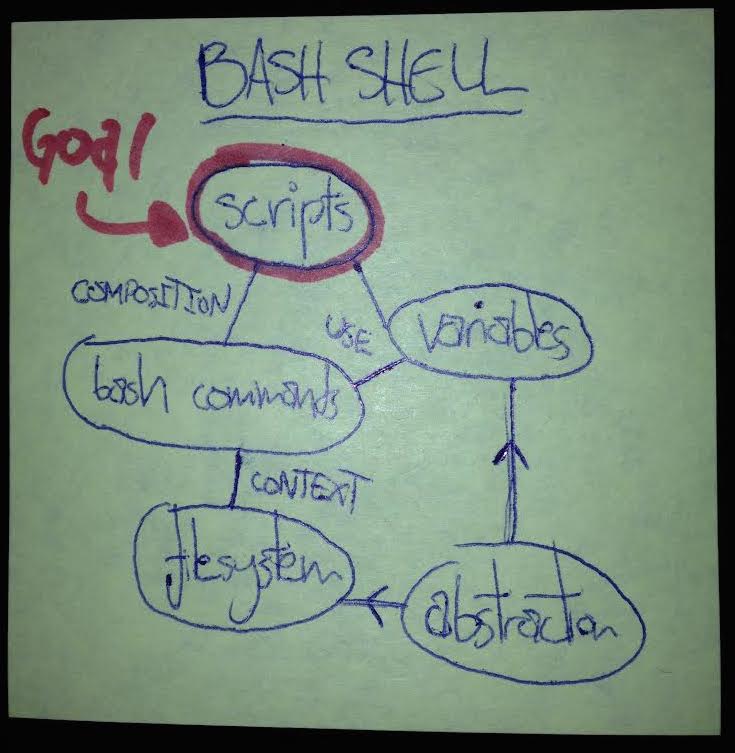

Identify Goals. Reverse instructional design is all about starting from where you want to get to. Choose the node or nodes on your concept map that you want students to have a clear understanding of after your lesson. Come up with some exercises or activities that will allow students to prove that they have mastered the target concept.

Characterize learners. When we think about concepts at the level of nodes on a concept map, we've got the flexibility to better match where our students are coming from. It can often be helpful to imagine a character that you think represents your student's experience and knowledge; in this way, you can not only match your learners well, but sometimes gain some insight into how they will react to lessons, activities and ideas. For example:

"Jennifer is a successful mid-career ecologist who has done most of her analysis using spreadsheet software. She's come to this class to learn how to augment her practice with a scripting language."

From this character, I can make an informed guess of what concepts are already understood; if I expect to have a room full of people with similar experiences to Jennifer, I might choose a few concepts from my map as starting knowledge:

Follow a path, from back to front. At this point, the lesson plan pretty much writes itself. Choose a path to get learners from where they are, to where they need to be - note that it's not necessary to touch on every node in the map right away!

Exercise

Perils

Reverse instructional design has great strengths in efficiently guiding students from where they are to where we want them to be - but there are some pitfalls in too fervently fixing our gaze on outcomes.

If you run out of time, you run out of time. A big part of reverse instructional design is mapping efficient routes to learning, without the distractions and detours inherent in plodding through every page of a topic textbook. But no matter how you plan your lessons, sometimes you just run out of time; discourse that takes a life of its own not only happens - it's the hallmark of an engaging learning experience. And if taking the time you need to facillitate that engagement and reinforce every concept well means you don't actually get to the stated destination, so be it. Remember: you are up there to teach - not to teach a particular topic. Smart lesson planning can help your students keep pace; racing to a premeditated goal will just leave them behind.

Beware 'teaching to the test'. Reverse instructional design emphasizes examining what students will need to learn in order to be able to successfully complete the final assessment determining if they reached the learning goals. This can sound dreadfully close to 'teaching to the test' - giving students so narrow a focus that they are able to navigate the final exam, and little else. The key difference is that instead of training students on rote problems to be duplicated on the final assessment, reverse instructional design done well builds up the student's concept map with enough strength that they can navigate new challenges using what they learned in the course; see to it that your final assessment includes such novelty, and we protect ourselves from teaching mere exam strategy.

A Note on Design Patterns

One other utility of design patterns we can learn from the software development world, is their use as a communication tool. If a document, be it a program or a lesson plan, follows a familiar structure, then future readers and users of the document will be able to more easily ingest that document, and know how to modifications to one part of it will affect the whole, per the prescription of the design pattern. For example, if someone takes your lesson and modifies the concept map, reverse instructional design immediately implies the concrete consequence to the corresponding lesson in a procedural way. This facilitates easier collaboration on lesson materials - a practice which while common and wildly successful in software, has yet to establish itself in teaching.

Assessment & Adaptation

By sticking rigidly to a script, whether it's a textbook, a set of notes or a lesson plan, we are essentially planning ourselves into a corner; that process relies on us being able to make reliable assumptions of our learners' knowledge, relies on our learners all having very similar needs so they can be served with the same lesson, and relies on us skillfully constructing what an adequate delivery technique will be. Instead, we want to conduct a more adaptive lesson; one that focuses on identifying & addressing our learners' misconceptions and gaps in knowledge in situ, and gives them multiple distinct opportunities to construct knowledge and understanding accurately and for themselves.

Summative & Formative Assessment

Any adaptive process requires observations to adapt to - so, we need effective tools to observe & assess student understanding. Student assessment is commonly grouped into two gross categories: summative, and formative.

Summative Assessment is intended to measure learning outcomes; the canonical example is the final exam. A well-designed summative assessment should reveal how well students have met the design goals of a course or lesson, as laid out in the first step of reverse instructional design; its principle use is for deciding if the course as a whole was successful.

Formative Assessment is intended to measure student understanding or ability in situ during a course, in order to adapt the course on the fly to optimise the efficacy of that course.

Superficially, these sound pretty similar, up to when exactly they are administered; they both assess student understanding & performance. The key difference between the two is resolution; in essence, summative assessment is only required to provide a simple up or down indicator of whether a course did its job or not; but formative assessment has to not only flag gaps in student performance, but resolve why and how students are missing the mark, in order to optimally inform instructional course correction.

Institutional western education has converged largely on summative assessment - principally because it's cheaper and easier. Summative assessment can be actualized in standardized testing, which can be administered uniformly at scale, with minimal interruption to already cramped classroom time, and responded to off line in future iterations of a course, as planning time and budget permit. But formative assessment is far more personal, deeper, and operational in real-time; it must be conducted on a per-classroom basis, typically during class time, and appropriate course corrections must be available at the instructor's fingertips. The scale that leads to summative assessment's efficiency is also its greatest weakness; differences between individual classes and cohorts get washed out, and adaptation is slow and can only converge toward a global mean. Formative assessment, though more labor intensive, is also far more nimble.

Exercise

Time is at a premium in the workshop environment. Taking time out to administer lengthy summative exams or in-depth formative investigations of student performance isn't feasible; we want the adaptivity aspired to by formative assessment, in exercises that take a few minutes.

Adaptation

So - you've just administered a quick formative multiple choice question, and the majority of your students are quite convinced that 37+25 = 512; what now? Formative assessment has zeroed in on a misconception; armed with that knowledge, what are some strategies for correcting the problem?

This is one place a densely connected concept map comes in handy. Presumably the first time you taught the misbegotten concept, it was introduced as a node on a concept map connected to some pre-existing scaffolding the students were comfortable with. Perhaps the connection originally explored was more obvious to some students than others; coming at the concept again from a different connection will reinforce the understanding of those that already get it, and give those struggling another run at it. If addition fell flat as a powered-up version of counting, re-examine number representation and the meaning of places and digits, for example.

Repeating nearly identical examples that follow the same lines of reasoning, on the other hand, not only adds little to the conversation, but runs the risk of being counterproductive, by reasserting the confusion that lead to misconception in the first place, thus potentially cementing it even further. The trouble being, that even the most creative instructor eventually runs out of ways to explain the same idea. How can we create a learning environment that's even more adaptive than we are?

Peer Instruction

No matter how good a teacher you are, you can only pitch a lesson at one level at a time, and phrase your oration one way at a time. In any class (but in open-signup workshops especially), students will come with a very broad distribution of skills and knowledge; the best we can hope to do with lecture alone is to hit the center of that distribution. But what about the tails?

Exercise

What you just did was an example of a technique called Peer Instruction, which goes like:

- Give students an MCQ, probing for misconceptions on the topic just taught.

- Have all the students vote publicly on their answers to the MCQ.

- Break the class into groups of 3-4, and have them discuss & debate the question within their groups.

- Reconvene & have the students vote again.

- If necessary, explain the solution to the problem, have the students return to their former groups, and discuss the problem again.

The first two steps of this recipe codify the use of a formative question to probe for misunderstandings, but the next three steps each add something more. By getting students to discuss their original answers, they are compelled to clarify their thinking enough to verbalize it, which itself can be enough to call out gaps in reasoning. Re-polling the class then lets the instructor know if they can move on, or if further explanation is necessary. A final round of additional discussion after this explanation then serves to give another chance for strong students to compile their understanding into something they can deliver as tutoring to their weaker peers.

This has numerous benefits. Our original goal was to make our lesson more adaptive than we (or any one individual) could be, and offer multiple different explanations of a concept to maximize students' chances of getting it; by employing the class, we get as many distinct explanations & phrasings of a concept as we have students who get it. Furthermore, those explanations are delivered in a personal and conversational context, so students who need the extra help get essentially personal tutoring in situ. What's more, the experience of teaching gives the stronger students the challenge and opportunity to make their own understanding so clear and well articulated that it can be taught to someone else. By infusing peer instruction into our lessons, we have used those hard-to-reach tails of the skill distribution to help each other.